In 2020 and 2021, anti-Asian racism in Canada moved into plain view. Incidents long reported within communities became part of the national conversation, fuelled by the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical rhetoric, and entrenched racial stereotypes. What became clear, though, was that this was not a short-lived surge. By 2025, researchers, community groups, and journalists continue to document discrimination, harassment, and widespread underreporting across the country.

This is where Anti-Asian Racism Undone, a scholar-led digital teach-in held in May 2021, becomes relevant again. Rather than treating racism as a crisis response, the event framed it as a structural issue tied to Canada’s colonial history, labour systems, and racial hierarchies.

We are not revisiting the teach-in to retell it. Our team treats it as a case study, asking what it revealed, how its ideas align with post-2021 data, and why its framework still matters in 2025 and beyond.

What Anti-Asian Racism Undone was and why it mattered

Anti-Asian Racism Undone took place on May 29–30, 2021 as a two-day digital teach-in organized through Scholar Strike Canada. The format was intentional. Unlike academic conferences that prioritize peer review and professional audiences, this event centred public education, accessibility, and collective analysis.

Teach-ins are designed to create space for dialogue rather than formal presentation. They invite scholars, activists, artists, students, and community members into the same conversation, flattening traditional hierarchies of expertise. That mattered in 2021, when many Asian Canadians felt spoken about but rarely listened to.

The event’s structure combined public pedagogy with abolitionist critique and cross-community dialogue. Discussions did not isolate anti-Asian racism as a single-issue problem. Instead, they connected it to broader systems shaping life in Canada.

Between sessions, a consistent thread emerged. Anti-Asian racism could not be understood without grappling with:

- colonial history and settler governance

- labour precarity and immigration policy

- gender, sexuality, and racialized violence

- policing, surveillance, and state power

- anti-Black and anti-Indigenous oppression

This relational approach distinguished the teach-in from many public conversations happening at the time.

Historical roots of anti-Asian racism in Canada

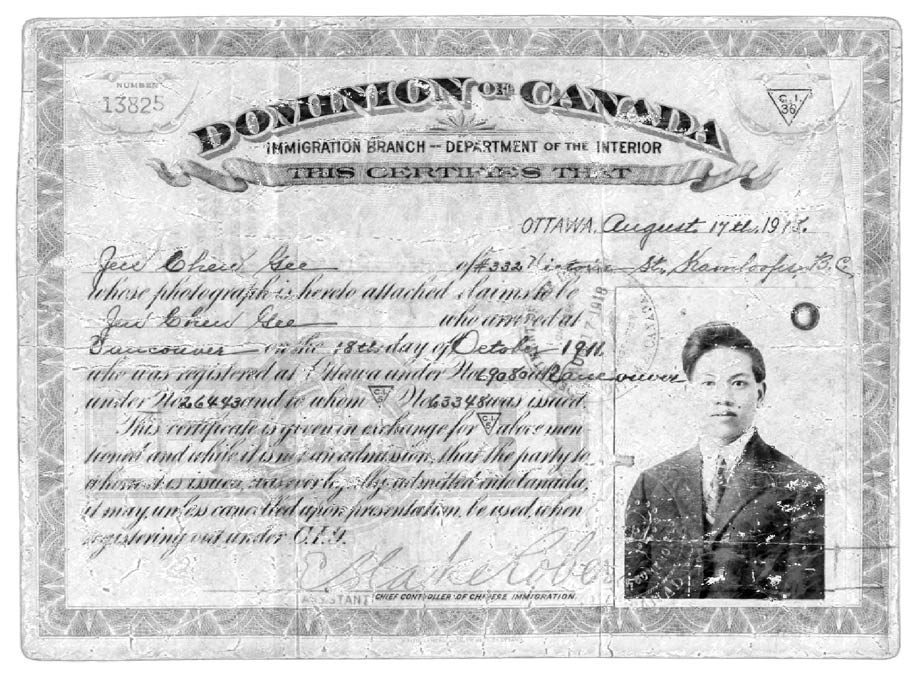

Anti-Asian racism in Canada is not new, nor is it accidental. From the late nineteenth century onward, laws and policies were explicitly designed to restrict, exploit, or exclude Asian communities. The Chinese Head Tax, Japanese Canadian internment during the Second World War, and the Komagata Maru incident were all state actions aimed at preserving a white settler society.

These policies were reinforced by cultural narratives that continue to circulate today. Ideas such as the yellow peril, the perpetual foreigner, and later the model minority shaped how Asian people were perceived and positioned. Each served a different function, but all reinforced racial hierarchy.

What changed in the twenty-first century was not the logic of these narratives, but their expression. During the COVID-19 pandemic, racial blame resurfaced through political language, media framing, and everyday interactions. In April 2021, a group of Asian Canadian scholars wrote:

“The pandemic serves as an opportunity for established, underlying currents of anti-Asian, and other forms of racism, to surface.”

Cary Wu et al., April 2021

The teach-in built on this understanding, placing contemporary violence within a much longer historical arc.

Why 2021 marked a turning point in public analysis

What set the 2021 teach-in apart was its clear rejection of individualistic explanations for racism. Violence was not framed as ignorance or the actions of a few bad actors, but as the outcome of larger systems. Scholars publicly examined the limits of Canadian multiculturalism, noting how it manages diversity while leaving racial inequality largely intact. They also highlighted racial capitalism, showing how economic systems rely on racialized labour while denying full belonging.

A major point of divergence from official responses emerged around policing. While governments often turn to enforcement after hate crimes, teach-in participants stressed that surveillance and criminalization have historically harmed Indigenous, Black, migrant, and other marginalized communities. As scholars involved in these discussions argued at the time, policing-based solutions risk deepening the very harms they claim to fix. The teach-in instead emphasized cross-community solidarity and shared vulnerability under colonial systems of racial control.

Core themes that shaped the teach-in discussions

The teach-in covered a wide range of topics, but several themes consistently surfaced. Rather than reproducing session content, we can summarize these ideas in analytical terms.

Anti-Asian racism as a product of white supremacy

Anti-Asian racism was framed as structurally linked to white supremacy, not as a deviation from it. This positioned Asian communities within broader racial power relations rather than outside them.

Labour exploitation and migrant precarity

Discussions highlighted how Asian migrants have long been channelled into precarious labour, from railway construction to caregiving and food services. Immigration policies were shown to reinforce vulnerability rather than mitigate it.

Gendered violence and racialized sexuality

The teach-in addressed how racism intersects with gender and sexuality, shaping patterns of violence, exotification, and invisibility, particularly for women, queer, and trans people.

The model minority myth

Rather than protecting Asian communities, the model minority narrative was identified as a tool that obscures inequality, denies structural racism, and pits racialized groups against one another.

Anti-Black and anti-Indigenous contexts

Anti-Asian racism was analyzed alongside anti-Blackness and settler colonial violence. This framing resisted competition between struggles and emphasized relational justice.

From criminalization to community investment

A central theme was the rejection of carceral solutions in favour of investment in housing, health care, education, worker protections, and community-led support systems.

What changed after 2021, and what did not

By 2022 and 2023, reported incidents of anti-Asian hate declined from their pandemic peak, but harm did not disappear. Instead, it shifted form. Online harassment increased, workplace discrimination remained underreported, and geopolitical tensions in the Indo-Pacific region added new layers of racialization.

Surveys from Statistics Canada, the Canadian Race Relations Foundation, and the Angus Reid Institute point to consistent patterns. Many Asian Canadians report discrimination but choose not to report incidents to police or employers. Distrust of institutional responses remains high.

One CRRF-supported analysis summarized the issue plainly:

“Nearly two in five Asian Canadians do not tell anyone about the racism they have experienced.”

Canadian Race Relations Foundation, 2023

This underreporting aligns closely with concerns raised during the 2021 teach-in.

Shifts inside universities

Universities expanded equity and inclusion language after 2020, but scholars increasingly faced constraints around political expression. Between 2022 and 2025, conflicts over academic freedom, DEI programming, and disciplinary measures became more visible across Canadian campuses.

Teach-ins, operating outside formal institutional structures, became an important space for continued dialogue.

Media coverage, more frequent but still shallow

Media attention to hate crimes increased, but coverage often remained episodic. Structural analysis of racism, colonialism, and labour systems continued to receive less attention than individual incidents.

New initiatives that emerged alongside scholar-led work

While scholars focused on analysis, community-based organizations built infrastructure. Several initiatives illustrate how post-2021 efforts expanded beyond teach-ins.

- CAAARC, the Coalition Against Anti-Asian Racism Canada, formed as the first national pan-Asian coalition focused on policy advocacy, research, and public education.

- ACT2endRacism and similar reporting tools created safer pathways for documenting incidents outside formal police systems.

- The Chinese Canadian National Council for Social Justice, through projects like #FaceRace, developed narrative archives that centre lived experience and public memory.

These efforts did not replace scholar-led analysis. They complemented it. Scholars articulated structure. Communities documented impact. Coalitions pushed for change

Where Anti-Asian Racism Undone sits today

Today, Anti-Asian Racism Undone is remembered less as an event and more as part of the archival history of scholar-led activism in Canada. Students reference it, researchers draw on its framework, and community organizers recognize its influence.

Its significance lies not in what it concluded, but in how it reframed the conversation.

What moving forward requires

Anti-Asian racism remains systemic. Addressing it requires cooperation across racial, institutional, and professional boundaries. Scholars, community organizers, and policymakers play distinct but complementary roles.

The teach-ins of 2021 did not provide final answers. They offered a way of thinking that continues to hold up under scrutiny in 2025. Learning from that moment means applying its insights to current realities, rather than treating it as a closed chapter.

And that, more than anything, is why revisiting it still matters.